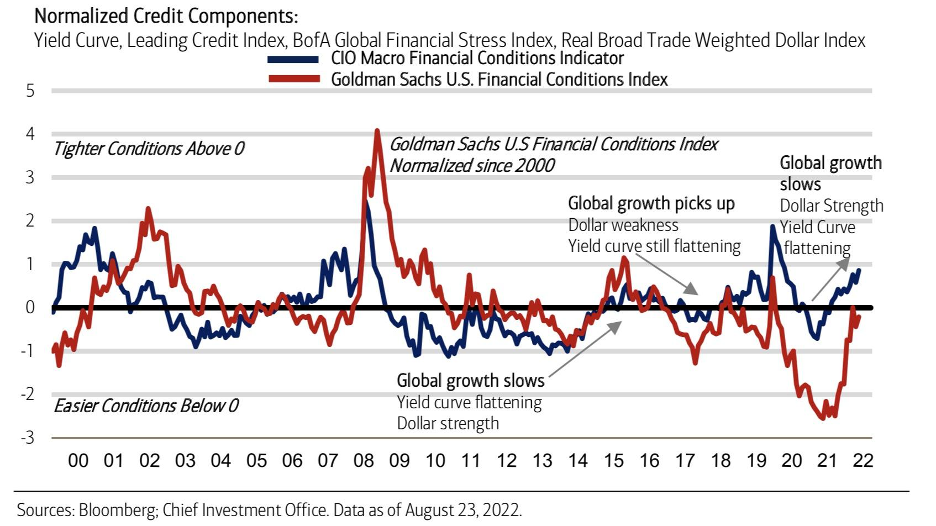

Well, Jerome Powell was pretty unequivocal, wasn’t he? As I wrote in my last piece, there was a win-win for him, given large rate hikes easing financial conditions (see below), so I wasn’t too surprised. For all people like Jim Cramer talking about inflation having peaked means buying risky assets are reading off an old Fed response function post-GFC script. The reality is that inflation has become more widespread, central banks have adjusted, and because messaging plays a role in forward guidance, they are unlikely to revert from hawkishness anytime soon. As Bill Dudley highlights in his Bloomberg piece , now it is about walking the walk.

The difficulties the Fed has been facing, however, are nothing compared to what the ECB is up against. Europe is in the middle of an energy crisis that tightening aggressively won’t solve. Still, given its single inflation mandate, the ECB will have to address and could also devolve into an existential crisis as it supports countries like Italy, where hedge funds are lined up in size on further spread widening. Suppose Powell admitted that US households and corporations may have to endure some pain to rid the system of the inflation menace. Can you imagine what ECB President LaGarde is thinking?

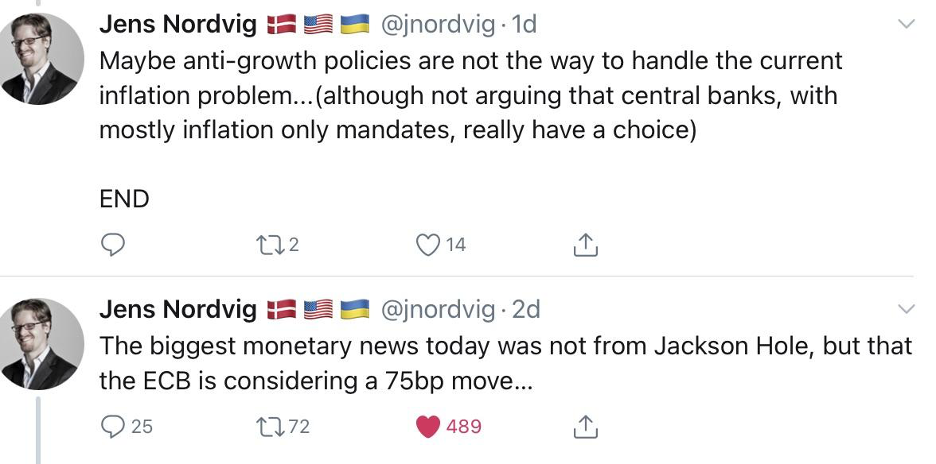

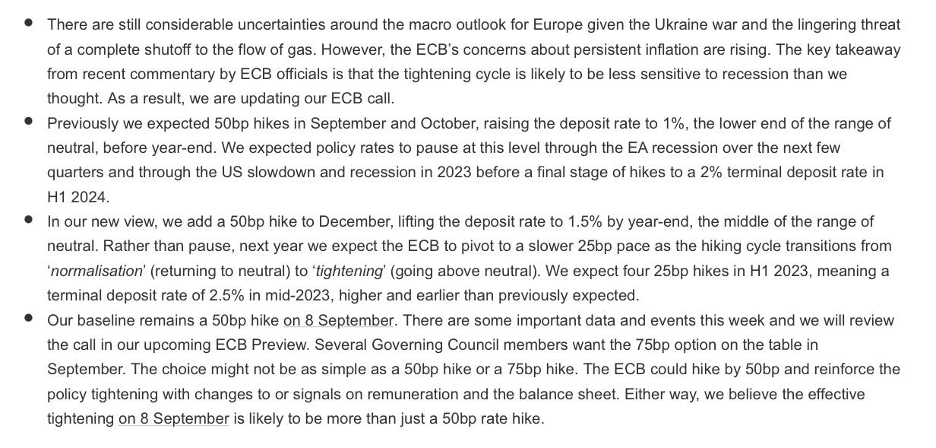

ECB chief economist Philip Lane is making the case for measured (ie. 50bps) moves until they reach a terminal rate of 1.5-2.0%, but the market has now priced in 75bps, which was also a big story away from Jackson Hole. As my good friend Jens Nordvig at Ex Ante tweeted, Europe is in a very tough spot:

And, for good measure, Deutsche Bank called for a terminal rate near 2% in the first half of 2024.

The net result of all of this is that there is (perhaps belated) some inflation-fighting gumption by leading CBs, but they are also about to open up some downside risks to growth and earnings, not to mention political fallout. What the market is coming to appreciate – and I outlined this several times showing the market pricing in a pivot for 2023 – is that looking through the current hiking cycle as a blip within a continued low inflation/dovish stance operating through the wealth channel, may be misreading the emerging fact pattern.

All of this is understandable because we have been telling stories and building narratives for quite some time to make sense of what is going on and why. In Bernanke’s “21st Century Monetary Policy” he discusses the late 1990s attempts by Chair Greenspan to explain (against internal Fed research) the prevailing inflation phenomenon (lower than expected and thus reason to stay loose) through the lens of greater productivity, which Bernanke (citing research from the likes of Alan Blinder, Janet Yellen, Alan Krueger, etc.) then goes on to suggest had only a partial effect since Greenspan’s views relied somewhat on a debunked theory called “worker insecurity hypothesis” suggesting productive workers valued security highly, and because there were more prosaic drivers including a stronger dollar, lower oil, methodological changes to inflation calculations, the advent of temporary workers, and Volcker/general Fed credibility and fiscal discipline. So, to insiders, the real story was less sensational and suggests Greenspan’s assessment of productivity was an untested theory (and productivity itself is very difficult to manage in service industries). Still, the narrative stuck, including that of Greenspan being a maestro. On that, recall that noted Watergate hero journalist Bob Woodward wrote a book entitled “Maestro: Greenspan’s Fed and the American Boom.”

I could come up with more similar popular narratives to make the point that there are a lot of unknowns/puzzles/mysteries out there in a complex system, and, critically, more and more research (think tanks, professors who served in government) to define the complex system is fraught with political biases (I will delve a bit more into that below around the student loan forgiveness policy). In any event, it is normal for investors to try to simplify complexity. We all develop heuristics, theories, and models, or we listen to and put weight on insights from people who have been right recently or succumb to other biases. Even so, just because narratives and theories appear to work for a time does not mean they will work in all states of the world. These are just not scientific axioms. Things change. I wrote in the last piece about why hiring portfolio managers with recent struggles can signify an inability to adapt.

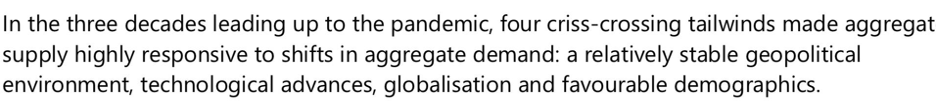

With all that said, here is a blurb from a great thought piece from the BIS’ Agustin Carstens that I wanted to highlight as he tries to implore policymakers to think much more about changes to aggregate supply factors forward.

And all of this is important because investors have to see the playing field as it is. The relevant golf analogy is that all the lies are perfect on the driving range, and there are no hazards. On the course, things are more challenging, and you sometimes have to play over water, from a sidehill/downhill lie to an elevated green surrounded by bunkers. Central Banks for decades have been trying to sell the idea they could tackle the business cycle, and even economic luminaries like Keynes and Fisher have remarked with impeccably bad timing that we may have reached nirvana. Once again, economic history is filled with examples of “generals fighting last wars,” only to learn that diagnosing the battlefield must account for the new reality.

It may well be that we are just in one of those periods where it was the perfect storm, and we all go back to buying risk assets without concern, as the issues Carstens notes above are overstated. But, as we are learning, we also have to account for the fact that these issues are durable and that making wise choices about energy policy, immigration, debt dynamics, demographics, supply chains, allies, geopolitical dynamics, communist countries’ “liberalizing” is of utmost importance, and the track record on policy is by no means inspiring.

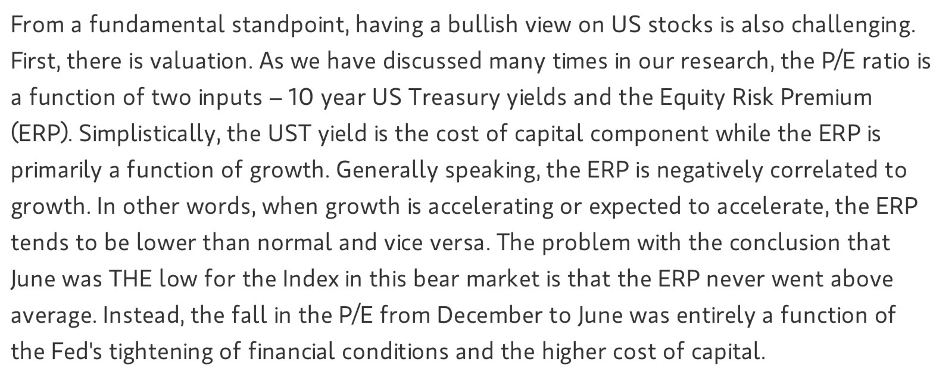

In that vein, I highlight Mike Wilson’s comments regarding equity risk premiums, which, together with global liquidity tightening, are headwinds for risky asset prices.

Things that caught my attention past few weeks:

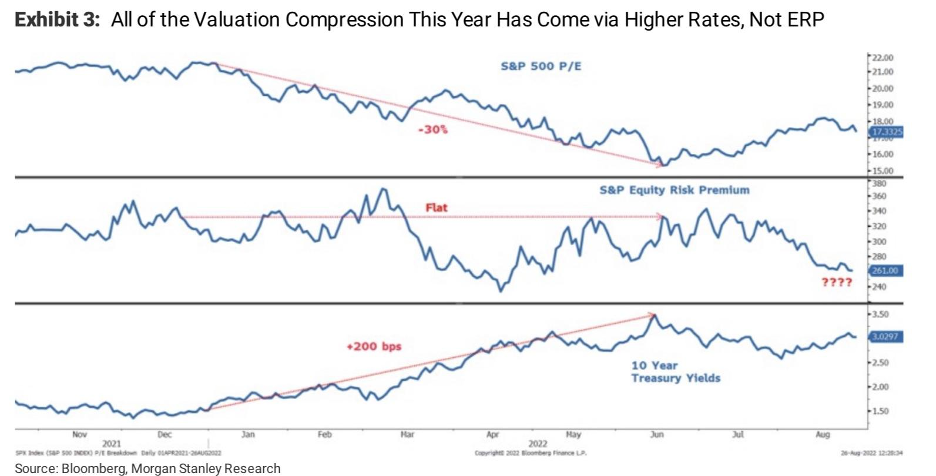

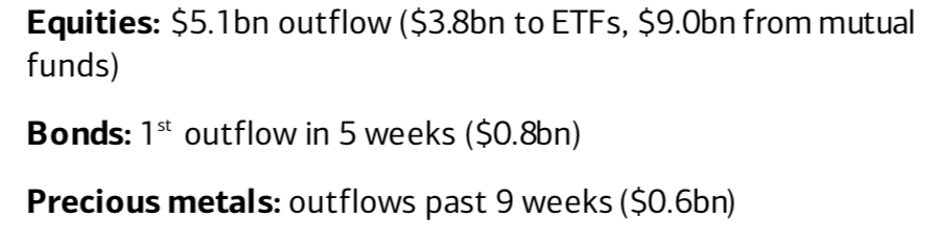

Flows and Positioning:

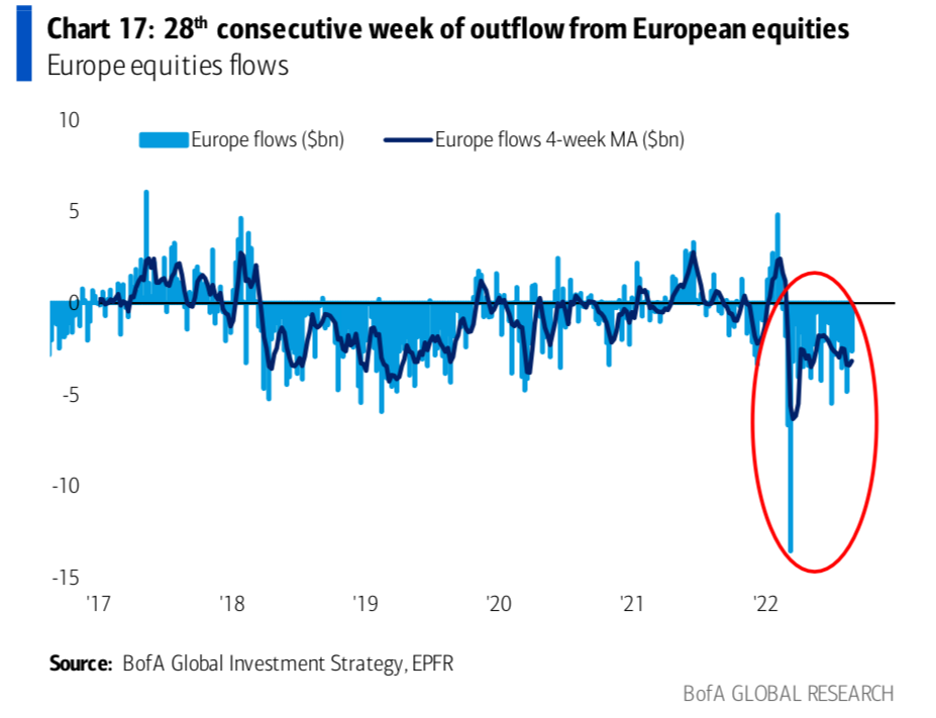

Worm seems to be broadly turning on the EPFR flow side for equities, with European outflows a bit of a trend. There was the first outflow from tech since Nov ‘21.

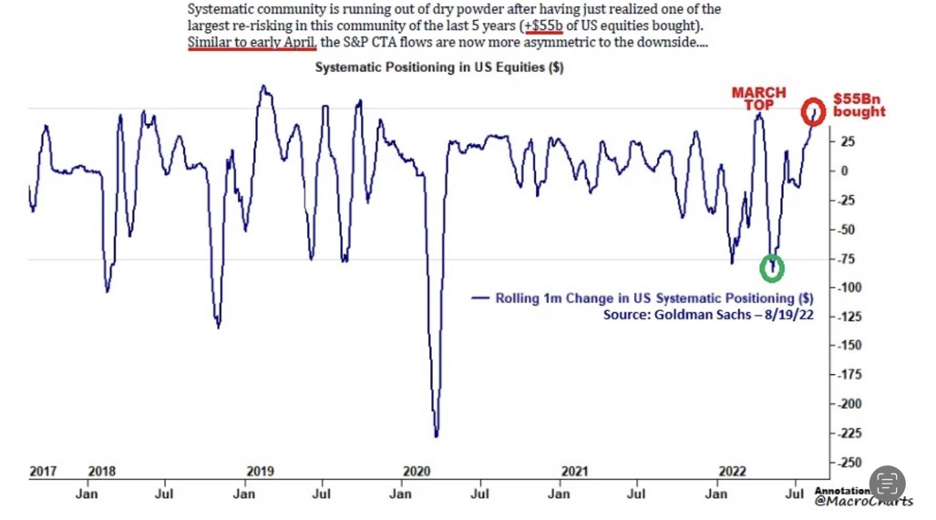

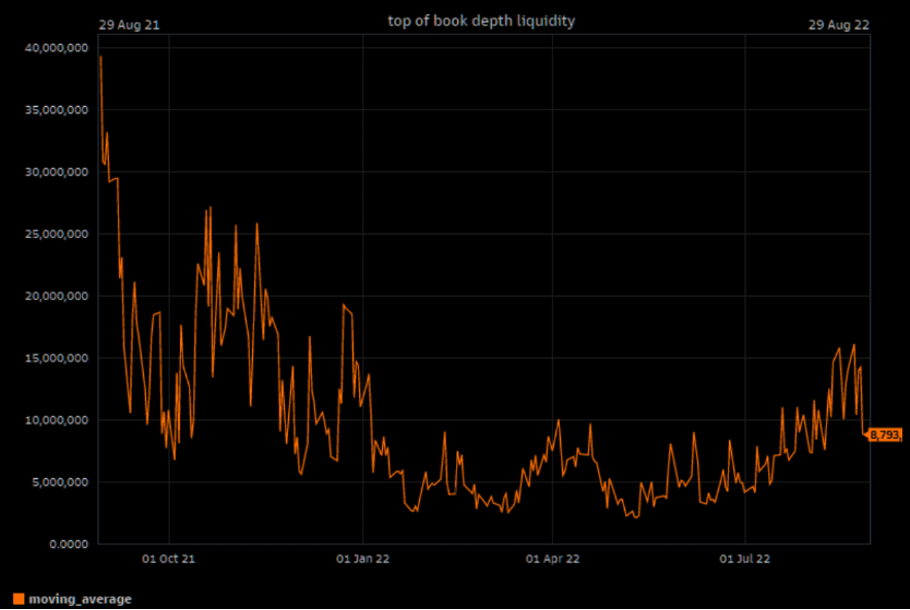

As I have been writing, fast money had been running the show as sentiment and positioning got slightly too negative, and Powell, etc., were being slightly less direct in messaging. Below, we can see that the systematic community (CTA’s, etc.) had been buying and are now in reverse mode post-Powell. Add into that negative gamma (max near 4000 S&P, 300 QQQ’s, but still negative), broadly crappy liquidity (see below from GS) worsened by a short week ahead of Labor Day, and retail overextension (with favorite stock Tesla down 13% since 3:1 split), so not surprised to see stocks falling and failing to get a bid. The corporate demand is still there, and if anything, given the IRA 1% tax has picked up the pace and pulled forward some buying, so that could keep a total rout from transpiring.

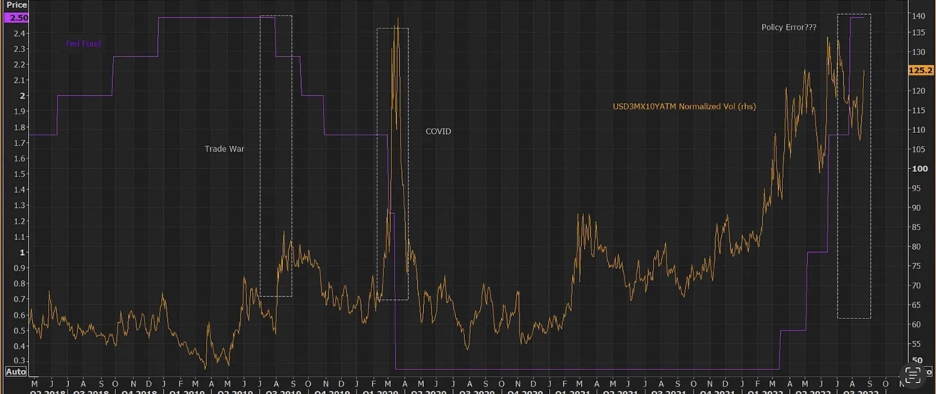

One thing that does have my attention is the relative volatility of rates and equities. These are interlinked markets but have different liquidity/volatility characteristics and different players/strategies. Either way, vol elevation in rates markets is likely about uncertainty about terminal rates, the pace of movements, economic impacts, and policy error – all things the equity market should be equally concerned about. I have some long VXX ETF that I have been adding to on equity rallies because I think the equity market is a bit complacent, and the pricing is decent.

On the VIX, DataTrek had a good table, which they presented with the idea that Powell’s speech was a 2 STD event, given that, that the VIX should be near 36 vs. 26 currently.

Another market showing some stress is the CCC credit market, which is another reason I have been buying what I think is somewhat mispriced equity volatility.

I think normalization – cruddy firms fail and are restructured and liquidated – will take place. Once again, I think credit markets appreciate the risk, but not so sure equity markets (which can be where credit risk hedging takes place) are in sync with that.

Bed, Bath and Beyond:

Welcome back to 2021. This was written ahead of the tragic news this weekend of the CFO jumping off a building and committing suicide. A lot will be written and talked about this week.

I got a note from a good friend who runs money at a major investment firm, and he noted that the volume in the name on one day was 2X the number of shares outstanding. It’s not a stock I follow, even though I have shopped there a fair bit over the years. That amount seemed like a lot and may be understated based on further reporting (see below). For comparison, AAPL has a daily average volume of 73m and has 16.25B shares outstanding. So, it takes roughly 222 days of daily volume to match overall outstanding shares and 444 days to match 2 times outstanding shares. It has a small short % of float at less than 1%.

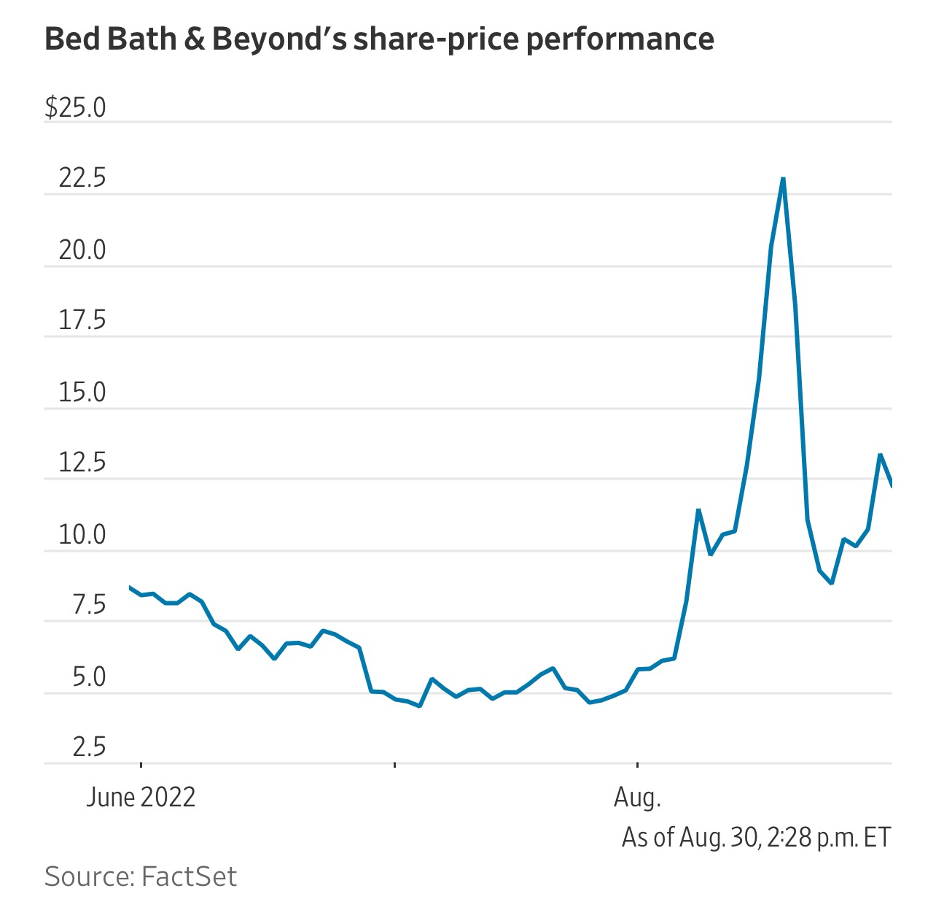

With BBBY, however, the average volume is 40M shares, and the float is 78m, with short interest at 29m. So, it seemed like a trading sardine, with an average 10-day volume of 2X float, so still, one day at 2X seems a bit out of the ordinary. It was ripe for a squeeze. All that was needed was a spark.

I mentioned in the last note that the retail crowd had returned to the market. It is not hard to see how this odd corner of the equity market operates. I have been caught up in a few squeezes where I play the wrong game. Luckily, I have gotten out without much pain, and in the case of Cathie’s garbage, others like Carvana, DoorDash, etc., have done quite nicely after the squeeze.

Overall, BBBY is a tale about how to protect yourself against attacks in an age of financial market “democratization,” easy trading access, social media, pack-like behavior, and an SEC totally out to lunch on policing these issues (more on that below). When I read the book “This is how they tell me the world ends” by Nicole Perlroth, it opened my eyes to cyber risks. I realized that the benefits of being online, 24-hour access to everything (banking, shopping, communication), have hidden costs. So, I try to protect myself. In markets, you have to know, as my old boss Louis Bacon used to say, “when you are the game…and you never want to be the game…” Louis was and is an avid outdoorsman/hunter, so that’s the reference. But, he also was insanely private and paranoid about the outside world, knowing his positioning – for good reason. He never wanted to be “the game.” That was a part of our role on the trading desk. Make sure we weren’t overexposed to potential gap-like risks due to excess positioning (relative to liquidity), and ensure we had outlets to get out. This was an existential risk to him, and I think Melvin Capital proves his paranoia was well founded.

Anyhow, back to BBBY, what confused me about this story was not the kid from USC that made $100m+ trading the stock (how many kids have access to the initial position of $25m?), but about the role played by the same guy at the epicenter of the GME debacle, Ryan Cohen of Chewy fame (for which he made billions). For a great piece on the matter, I refer you to Doomberg.

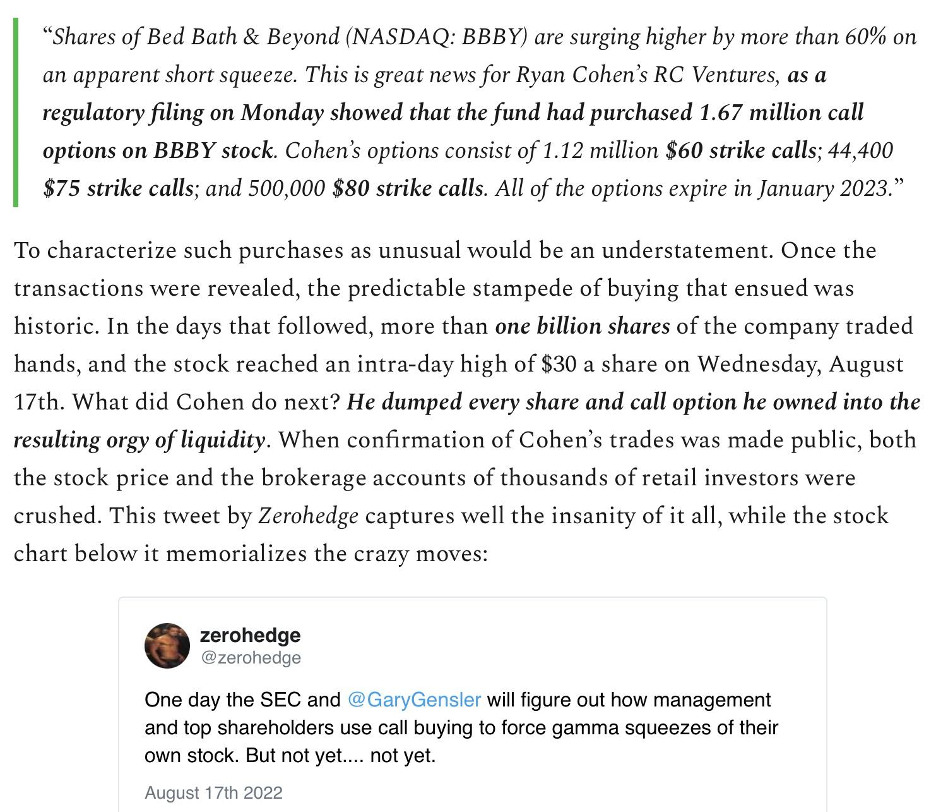

Cohen used the GME playbook (struggling retailer, activist investor) to excite the retail investors by obtaining a stake in the company. BBY had a large short interest (well, because it was expected equity holders wiped out in bankruptcy). To add insult to injury, Cohen did the following, which disclosed large, deep out of the money call options via the SEC.

And, when the retail crowd piled in, he used that liquidity to exit. That’s a good old pump and dump. Anyway, here is a snippet from Doomberg’s piece explaining (somewhat incredulously) what transpired.

I understand the moral logic of some of these retail guys. They believe the game is rigged, so why not collude and run shorts over who they believe are morally bankrupt? But bad businesses are bad businesses. It is not the short sellers’ fault a company does not execute with the concern that a competitor will eat their lunch. The short seller is there to highlight asset misallocation and sometimes provide liquidity. It should make the market more efficient. As I alluded to above, owners of distressed credits may short the stock because they are naturally short puts on the company’s value. Creditors are what BBBY needs on a going-forward basis, so one wonders how these situations ultimately help distressed companies. In the meantime, the SEC has to do something about this all. The stock is nowhere again, and the company is still performing poorly (as is AMC, and GME), but some have gamed the system to their benefit.

Maybe Gensler’s pleas for more transparency about short sellers is about trying to clean this all up. Still, it would be helpful to see some investigations into these incidents (and all the gamma buys every week in names like Tesla, etc.) and exactly who is trying to drive these market movements because markets are not supposed to be a casino and video game. There are some very big fish at the end of these blatant gamma squeezes, as Doomberg rightly notes.

Deficits and Debt Part II:

In the last piece, I wrote about deficits and debt – which understandably is a bigger issue and has that gap-like characteristic of not being important until it is. In that way, I was putting the topic on your radar screen. Why? Because I still think there is massive confusion about price levels and inflation and the role of monetary and fiscal policy in that regard. I have no axe to grind politically – as I have said, I find them all objectionable to an extent – I just want to help investors appreciate the complexity and causality are deeper and more nuanced than commonly articulated.

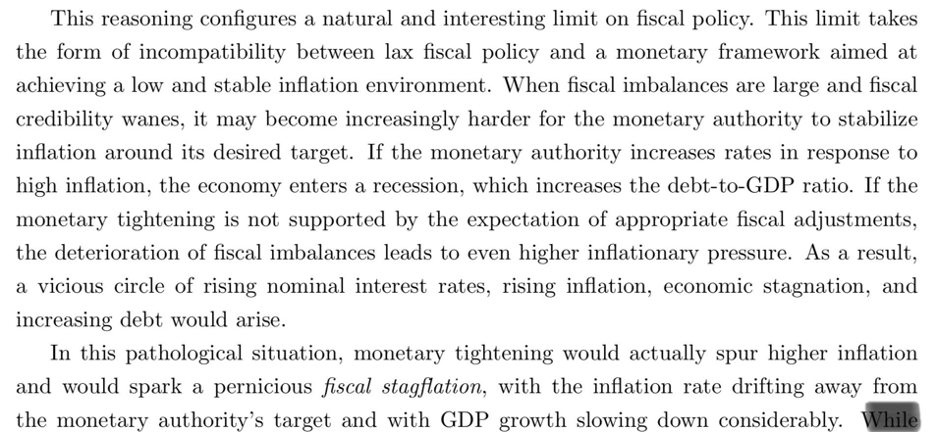

Anyhow, Of the many good pieces at the Jackson Hole event (yeah, it’s not just Powell and the Keynote), there was a piece that precisely characterizes why I included it in my last note, which relates to fiscal stagflation.

Here is a quick Bloomberg piece on the paper for reference.

I would read the paper and skip the math. It’s ridiculous that one needs advanced math degrees to read papers. Still, when you are trying to prove cause and effect and whether variables have statistical explanatory value, it’s hard to escape that.

From the layman’s view, I try to take off all this is that money. Debt/credit is needed to drive the economy. Still, there are natural constraints – labor, capital, and technology (and, of course, the conditions that provide for optimal functioning) – and inflation is a telltale sign that the situation between aggregate demand and supply has gotten out of whack. It is not just money supply but credit, and the movement toward high caliber investment (in supply capacity) must be in line. The Fed has to do its part, but so does the government.

What people don’t appreciate is that when Volcker did his thing, Reagan was not just cutting taxes and spending on defense; he was talking about reducing the size of government and focusing on incentivizing supply, which had the effect of being directionally similar to monetary policy, and in general fiscal discipline was seen as a bipartisan issue post-Volcker/Reagan given the experience of the 1960’s/1970’s. The directional similarity is important because deficit spending is the country’s credit card, and the balances need to be paid down. That’s the whole fiscal theory of the price level – that willingness to accept fiscal policy credibility matters. I am not dismissive of other parts of the Reagan agenda that may have materially moved the power balance between labor and capital/financialization of the economy and caused other issues. Just to say that beating inflation is not just a Fed issue.

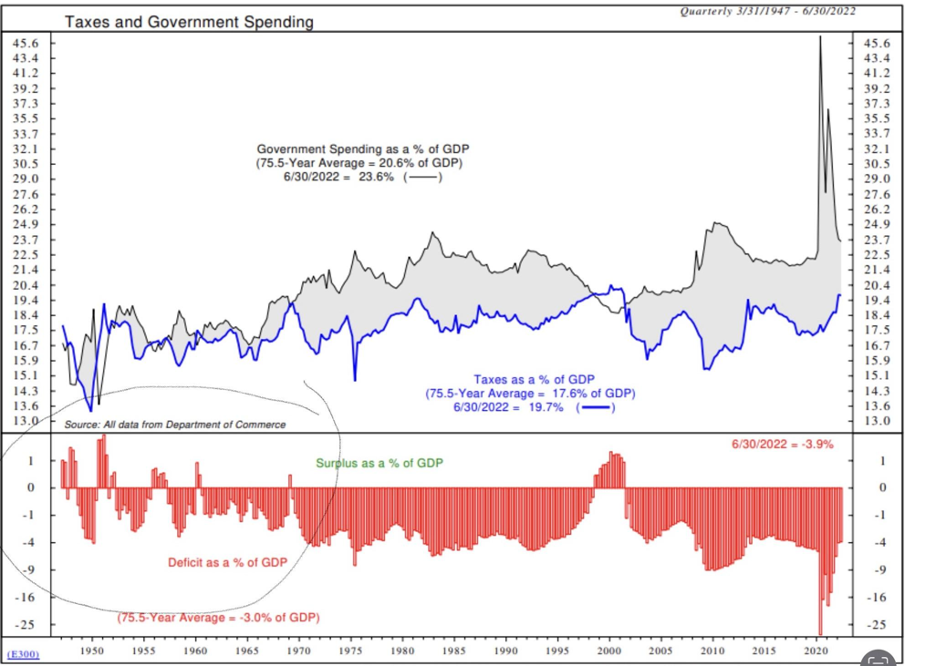

And, as you can see from below, coming out of WWII, managing deficit and debt prudently were in sync. Financial repression, inflation, the Fed funding deficits, etc., and fiscal credibility/prudence. You can see the late 1960’s/1970’s and recognize that the average deficit of the period was increasing relative to the past, which, combined with other factors, helped to bring about an awful period of stagflation and the introduction of the misery index (inflation + unemployment).

In the 22 years since the turn of the century, average deficits put the past periods to shame. Of course, there have been events – 9/11, wars, GFC, Covid – that have put us in this situation, but that does not mean fiscal sanity is unimportant. And while some are mentioning that fiscal discipline has returned because current deficits are moving toward long-term averages, we still have an issue that, as the paper above shows, matters to our current and future plight because our debt load is similar to that of immediate post-WWII. Our mindset – and certainly our opportunity set for growth – is not.

Student Debt Forgiveness:

Jeez, where to start? Firstly, I see this as a political move primarily because it is unclear whether this action is legal. The Supreme Court, in its ruling on West Virginia v EPA, kind of gives some sense that administrative orders that veer from the original intent to push agenda items will not be favorably viewed. So, in that vein, it’s a win-win for Democrats to try to push for debt forgiveness because a. Shows willingness to fight for this cohort that has legitimate issues to deal with; b. If struck down by conservative courts – already the enemy given Roe – they incentivize their base.

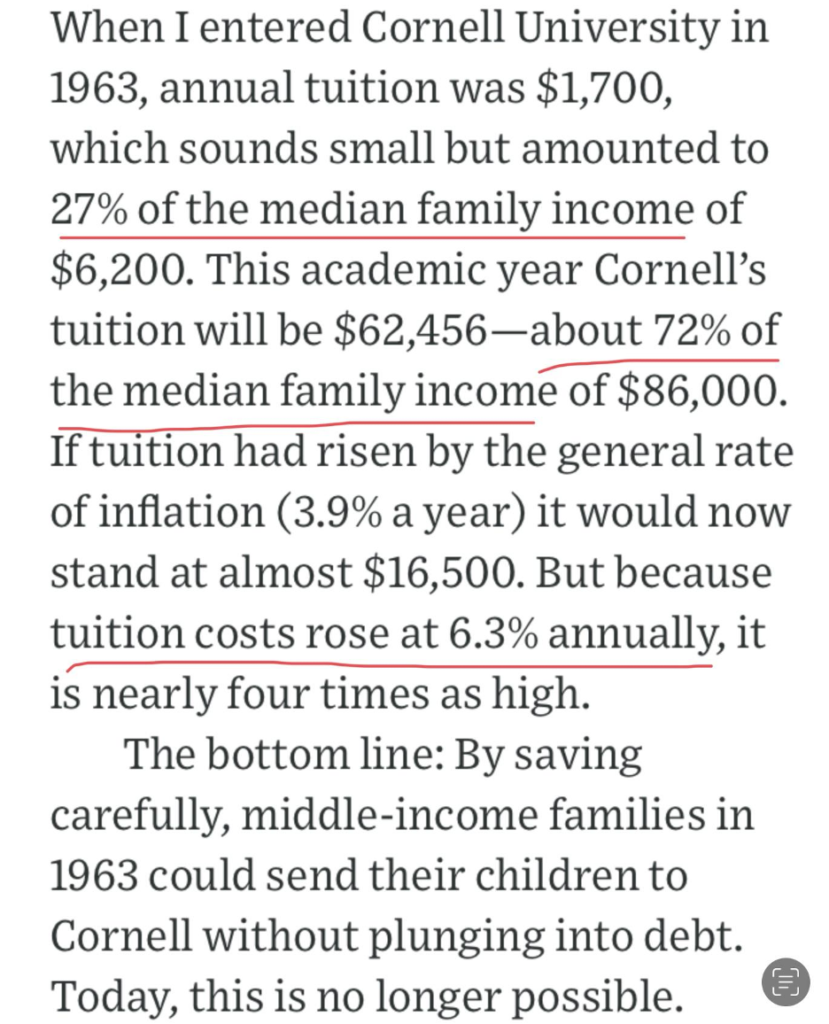

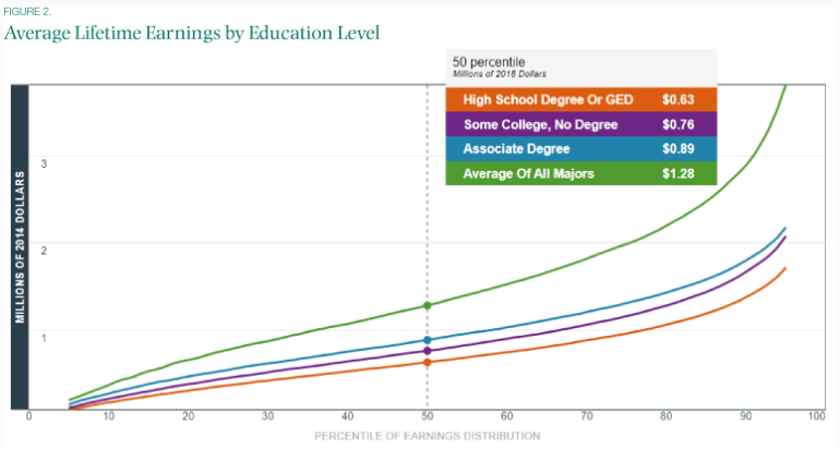

The arguments and justification I have heard from the Administration and supporters that this is giving relief to overburdened graduates – partially bailing them out – and akin to a tax cut is whatever. We lost the plot a while ago with fiscal sanity, straw man arguments, and other “what about” excuses. The problem with this plan is that it does not do anything to manage the pressing problem of college costs and has the potential to make it worse on the one hand, given the tight relationship of debt availability (changing income repayment plan from 10-5% is a big deal) and costs, and to have further federal encroachment of the university experience on the other. There is enough data with public K-12 to seriously question whether this encroachment would help or hinder.

And, to be sure, I have great sympathy with the college cost problem, having just spent close to $500K to send two kids through school. Yeah, am I a bit upset that I didn’t have my kids take on some debt so they could have benefitted from this action, or just about general fairness given my wife and I paid our loans back – and for a while, it was not fun or easy, or moral objection because making financial commitments should be respected. They are held accountable for their personal choices, and those who choose/cannot afford not to attend college will be paying for those who do, sure. On that last point, I refer to an outstanding piece by Jared Dillian on the matter. For a broad piece on how the cost problem could get worse, see Megan McArdle.

As a Pell recipient myself, I am extremely thankful for the education I received as a kid from lower middle-class Queens, and I do believe that kids these days are screwed if you add up the overall cost to launch (education, initial housing + broad career opportunities/initial pay outside of narrow segments). My daughter works for Ross Stores in NYC in retail planning, and if she did not have some financial support from family and student loan balances, she would not be able to live in a safe place and/or manage without building big credit card balances. Mind you, because she knew this was the type of career she wanted (retail, marketing, media) where first jobs are painfully underpaid, she chose to attend Indiana (Kelley Business School) because she got a partial scholarship and her overall cost of matriculation was materially less than private. She had other private universities she could have attended, but we collectively chose that for her, the savings of IU vs. private would be plowed into early career living. But, these clear-headed choices were made by not only engaged and somewhat knowledgeable parents (with financial means) but also a very mature young adult, which might not be the plight the average family faces.

Anyhow, here is a good article from William Galston of the WSJ that, while remarking correctly that this is likely to cost a whole lot more than the $300B being reported and another on the games that will be played going forward given the action, the point Galston makes is to me the most relevant.

Galston makes similar points about public education, although in-state tuition is a great deal, while impacted by reduced funding and similar inflation issues to privates.

So, taking all of this together, keeping in mind the section above on deficits and debt and broader points about coherency in policy that are democratically agreed upon and constitutionally consistent (legislation drives the purse), I tend to view this as a somewhat cynical approach to a pressing problem with wider ramifications, and reflective of broad political and systemic decline. That it adds to the deficit and inflation when the administration just put forth the Inflation Reduction Act and has all sorts of potentially larger costs is concerning. That it is a backdoor way to put in place free community college and full university education without nailing down the cost equation/controls and has the feeling of a new entitlement (where our track record is not hot in terms of quality/cost), is even more so. We have clear processes for these things, which feels like when the Baltimore Colts moved out of town in the dead of night.

The only positive I see to what they did is it will shine a big light on the problem because if parenting has taught me anything, it is that if you do something for Kid 1, you better do it for all. So, the probability of this becoming a recurring theme is high, and because of that, it could theoretically encourage coherent action – but that may be a charitable view.

Fwiw, I had a lot to say about how to manage college costs, or the debt situation, that I cut out, but the main things I would stress would be:

- Student debt discharged in bankruptcy

- Increase Pell Grant sizes and availability

- Encourage universities to follow Brown’s example – no student loan for incoming students funded out of the endowment

- Rid schools of administrative bloat / streamlining

- More 3-year programs – similar to Europe – which is more focused (i.e. Concentration based)

Other Tidbits

Buybacks:

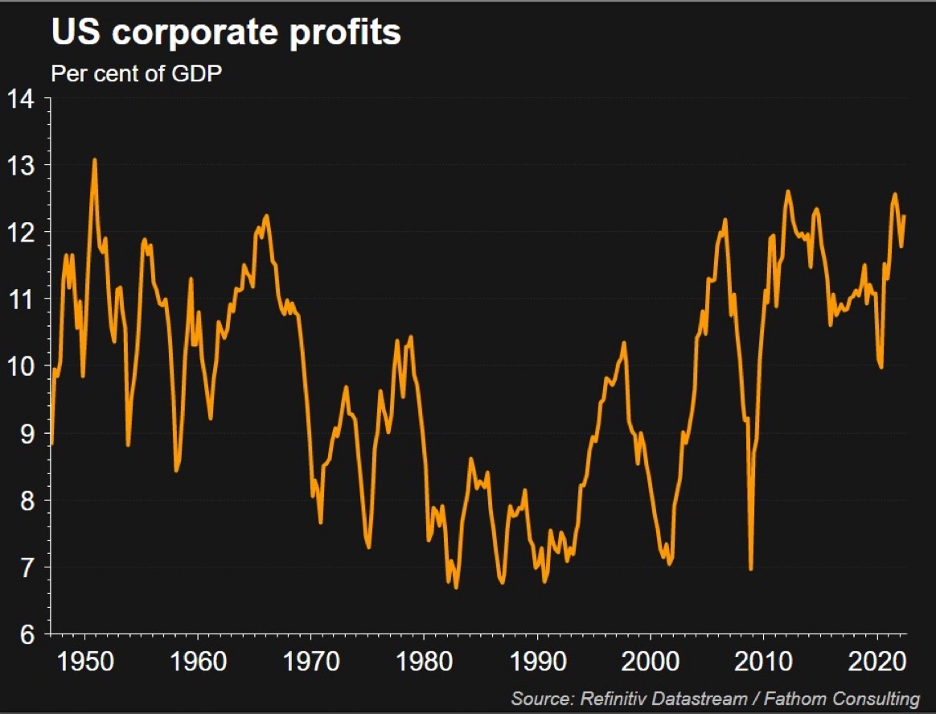

As we know, the IRA had a 1% tax on buybacks. Using the logic that if you tax something, you get less of it, the tax implies something is wrong with buybacks. I appreciate that (as I talk a smidge about below) corporate profitability ought to be recycled into people, capital investment, and future productivity. Still, buybacks do get a bad rap, largely because they are mischaracterized at times and because capital investment in a service business (capital lite) should include intangibles and R&D. If they were, it would show capital investment is fine.

I worked at CSFB with Michael Malboussian (so familiar with his writing), who is now at Morgan Stanley and writes a great piece called The Consilient Observer but is also a well-respected adjunct professor at Columbia School of Business in their top-notch Value Investing Program, and he penned a good piece on buybacks. For craps and giggles, go through the comment sections to see the incredibly vapid comments on what is a solid piece. If politics is about putting in place the public’s will, it generally is helpful if the public’s will makes sense. Politicians are supposed to override silliness and mob emotionalism. On both sides, they rarely do these days.

Regulatory Focus:

I touched a bit above on the SEC in the BBBY section, suggesting a lot is going on these days around Gensler, and none seem too focused on things I typically pay attention to – like market efficiency/fairness. Did anyone realize they have been hiring economists nonstop to support and testify on their rule changes?

When I first started writing, it was about the time Biden came into office, and I said there were a handful of things that his administration would try to address (directly or indirectly): Climate, Infrastructure, Education, Inequality, Capital vs. Labor, AntiTrust, Stakeholder Capitalism, Reparations. I don’t see any less resolve, and I don’t view them as broadly favorable for growth and earnings. If you throw in that the IRS will tie up more businesses (many small) via audits, it’s clear the path this is all on. a. Corporate profitability is doing well (see below), which has to drive people crazy in DC and state capitals to get their hands on more of it; b. Get it into the hands of more workers/labor.

Anyhow, here are two articles that speak to these topics. Not making a political point, just an economic one. We need regulations, and we need them to keep pace with the structural shifts, but there are always costs.

Wall Street Rails against SEC regulatory Agenda

US Trust Busters taking on Private Equity

Has California lost its collective mind?

This relates a bit to the above on corporate profits and revenue sharing. I don’t know the specifics on whether these people are underpaid or not relative to their marginal productivity, but assuming the market is a better driver of sorting this stuff out than a control board, it is certainly not a move in the right direction.

Midterms:

I think the Democrats are on a bit of a roll as Biden’s approval numbers are moving a tad in the right direction (although still bad and still likely portends a bad midterm outcome) and using the polarizing red-haired guy as cheap leverage (see Ben Shapiro quote), but whether that is enough will be a question. Certainly, the abortion thing – as I suggested – is having an impact. Here is an article written by an old friend who used to throw batting practice to us at Brown (where he was a graduate student) that speaks to the momentum we are seeing and some mistakes the Republicans are making; and well worth reading.

Food for Thought:

What Changed?

Book(s) I am reading:

Edward Chancellor – The Price of Time